- Home

- Robert Gipe

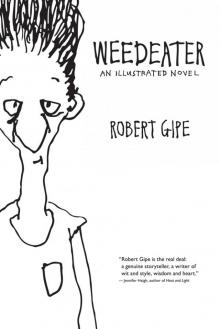

Weedeater

Weedeater Read online

Weedeater

WEEDEATER

AN ILLUSTRATED NOVEL

ROBERT GIPE

OHIO UNIVERSITY PRESS

ATHENS

Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701

ohioswallow.com

© 2018 by Robert Gipe

All rights reserved

To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax).

Printed in the United States of America

Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ™

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gipe, Robert, author.

Title: Weedeater : an illustrated novel / Robert Gipe.

Description: Athens, Ohio : Ohio University Press, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058087| ISBN 9780821423097 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780821446256 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Coal mining--Kentucky--Fiction. | Dysfunctional families--Fiction. | Drug abuse--Fiction. | Domestic fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3607.I4688 W44 2018 | DDC 813/.6--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058087

Dedicated to the memory of my mother

Barbara Jane Hale Gipe

1939–2016

Contents

1. Dreadful Crash

2. Ruckus

3. Airplane Girl

4. Dry It Up

5. One Good Reason

6. Running Coal

7. Spray Paint & Burn

8. What Was What

9. Already Dead

10. Floathouse

11. Coaltown!

12. Where Witches Come From

Acknowledgments

1

DREADFUL CRASH

GENE

First day of July I was thumbing the Caneville Road. I’d walked off another of Brother’s cleanup jobs, mine sludge up to my pant pockets, throat raw, hands itching and broke out. For eight dollars an hour I told him I couldn’t do it. Told him I’d walk back to Canard. He didn’t like it and called me an ugly name, but I told him I’d make it up to him, and at the time I thought I would.

I got my first ride from a blackheaded man in a Chevy pickup. He set me out at the Caneville bridge, and I stood there a good while, till a heavyset preacher picked me up, but he got a flat before we got to Pic-Pac and had to call his wife to bring the spare. I went in Pic-Pac and got me a Popsicle, come out, started walking. I walked a half mile when a man stopped had the crazy eye. I told him I’d wait, and he gunned his silver Buick across the double yellow line into a red Ford heading the other way. The Ford flipped up on its side against the rock wall, and the Buick sailed down the ditchline toward Canard a hundred yards and hung up on a road sign, front wheels spinning, no skid mark in sight.

Such as that common in oh-four, back when the pain pills poured down like February snow. Same year one died in a bathtub dry and blue as a pool chalk. Another they found dead in the sewer ditch in front of the Frawley Headstart. A lady’s heart give out, a needle in her arm, back of the Christian Church, and a teacher died at Kettle Creek School snorting a pill off her desk in front of a room full of kids. All that in Canard County in a single year.

When you’re first one at a wreck, you can’t believe how quiet it is. A woman had hair dyed orange come hollering out of the sideways Ford, but even still it felt too quiet. No police nor ambulance. Just you and what happened. A man with a winch on his truck come up, had a hat said “Blackbird VFD,” and he went to work getting that Ford set down. Then a lady in her hospital scrubs stopped, tried to see to that screaming woman. After that, people gathered from every side—come out of their houses to say they seen it, cars lined up down both sides of the road full of people wanting to help, a man running for magistrate handing out cards. Pretty soon so many people had congregated, felt like a yard sale. One woman stopped to ask if anybody was selling baby clothes, but when the ambulance pulled up and she seen it was a wreck, she started to cry. I told her not to feel bad, told her I thought the very same thing.

When she settled down, I walked back to the Buick. They was several people crowded around, and I could barely see the driver the way the Buick was rared back on that road sign. I stood up on my tiptoes, and seen the man stir. He stared out the windshield at the white summer sky.

Somebody said, “You gonna make it, buddy?”

The man in the Buick leaned over on his elbow towards us, mouth hanging open, face white as the sky. His eyes opened wider, till they was like two bowling balls coming down the alley. He shook his head back and forth and said, “Nope.”

Then he lay his head down on the car seat and didn’t move no more.

Somebody said, “Did he die?” and I turned to see who it was. That right there was the first time I seen June. God, she was good-looking. I fell in love on the spot. I got to where I couldn’t bear to say her name. I just call her That Woman.

That Woman stood there with a big tall girl, her niece, name of Dawn. When I didn’t answer June about the man dying, Dawn said, “Say,” so hateful all I could do was stand there and look at her big wild head of hair.

DAWN

“Say,” I said, and Gene just stood there, his arms brown as bread, covered in gray mud, every other finger mashed up. He smelled like he’d bathed in lighter fluid and looked like he’d been drug through the landfill. He turned to us, eyes all misty. I thought he was fixing to cry.

I said, “You fixing to cry?”

Aunt June told me to hush. I was sorry for that man being dead, and I shouldn’t have been hateful to Gene, but I was in a terrible mood. It was too hot to be married. But I was. To Willett Bilson, a man I’d courted on the Internet. I had my little girl Nicolette strapped in the car and Aunt June’s yellow dog Pharoah pulling at the leash. Willett hadn’t turned out like I hoped and I had moved to Tennessee for him and now this Gene was gawking at Aunt June, and they was dead people scattered all over, and it was too much. I’ll just be honest.

Gene walked with us back to June’s car. “If I’d rode with him,” Gene said, “this might not’ve happened.”

I said, “Or you’d be dead too.”

“I’m Gene,” Gene said to Aunt June.

“Hello, Gene,” Aunt June said.

Pharoah barked.

“She’ll bite you,” Nicolette said to Gene. Nicolette was four.

Gene put his hand down to Pharoah’s mouth. Pharoah raised her lip.

Gene said, “That’s a good dog.”

June looked off at the Ford. The orange-headed woman standing beside it was screaming, “Save my baby. You got to save her.” A woman in hospital scrubs had her arm around the orange-headed woman. A truck had winched the Ford back down onto the road.

“How’d you get here?” Nicolette said to Gene. “Where’s your car?”

Gene said, “Aint got nary.”

June said, “You need a ride?” June loved a project. She loved saving stuff.

I loved it when it rained and everybody stayed home. Gene moved to get in the car. Then he stopped and spoke.

GENE

“I don’t know you want me in your vehicle,” I said. “I aint what you call fresh.”

That Woman said, “We aint that fresh ourselves.”

Niece Dawn said, “What’s that all over your pants?”

I said, “That’s from helping Brother clean tanks.”

Dawn said, “What tanks?”

The little girl said, “Army tanks.”

I said, “Tanks held coal float.”

Dawn made a face like she’d opened something spoil

ed, looked at That Woman.

That Woman spoke to her niece a minute and then That Woman took the dog and the little girl and Dawn opened the trunk and pulled out painter dropcloth plastic, started spreading it in the front seat. A Dabble County sheriff’s cruiser pulled up and a deputy got out, asked questions of the people gathered, must have been fifty by then. Out the side of my eye, I seen the woman in the hospital scrubs pointing at me. The deputy come over and asked had I seen it, and I said I had. He asked what I seen and I told him and he stopped writing in his little book, folded it up, said, “Now what was it you were doing out here?” and looked me up and down like there might be something to find out about me, but there wasn’t. I was just walking off a bad job like anybody with the least regard for theirselves would, and I don’t know what I said to that deputy exactly, but he leaned his head forward like somehow I had some part in that bloody mess.

About then, That Woman said, “You holler when you’re ready to go, Gene.” When that deputy looked at That Woman, she leaned over, picked up that little girl and moved that dog leash to her other hand, said, “We’ll be waiting for you.”

The deputy flipped back through his notebook, said, “I can get ahold of you at this number,” and turned the notebook towards me, showed me the number at Sister’s house. I said he could. He nodded and I said, “It’s OK for me to go?”

He looked at me, waved his hand had the little book in it, said I could go.

DAWN

You had to be hemmed up in the same vehicle with Gene to appreciate how bad he smelled.

I said to Nicolette, “Stop rubbing your nose.” We were sitting in the backseat with the dog. Gene and June were up front.

Nicolette said, “I caint.”

I said, “Yeah, you can,” and set her hand down in her lap.

Gene said, “What’s this?” He turned, reached across the seat, and held a piece of glass up between me and Nicolette.

Nicolette said, “Where’d you get that?”

Gene said, “Off the road.”

The glass was blue-green clear, like old pop bottles, rubbed smooth like water’d been running over it, like it had been somewhere it could tumble. Glass going back to sand.

Gene said to me, “Can she have it?”

I said, “I reckon.”

Gene reached the glass to Nicolette. She closed her hand around it, and then dropped it out the window. June didn’t see it. Gene didn’t say nothing. Nicolette grinned like a half-shucked ear of corn.

Aunt June said, “Where you going, Gene?”

“I’m staying at Sister’s,” he said. “My sister’s.”

Pharoah growled. Gene looked back at her.

“Be careful with her,” June said. “She’s liable to bite.”

Gene stared at Pharoah. He had a face like desert rocks in a cowboy movie.

“That’s a good dog right there,” he said. “She’s looking after you. That’s what makes her growl.”

Pharoah was a sweet yellow dog, but crazy as a bestbug.

“What’s that on your face?” Nicolette said.

Gene put his hand to the cinched-up black spot on his cheek, said, “That’s where they cut off my hairy spot. Said it had the cancer. Where I’m out in the sun so much.”

June’s eyes filled the rearview.

Gene said, “Something like that make you appreciate.” His eyes stayed on us, blinking like somebody was squirting water in his face.

“How can you sit turned around like that?” I said. “Makes me carsick.”

Gene put his hand to Pharoah. She laid her ears down, and he scratched between them. “Does me too,” he said.

I turned and looked out the car window at a cornfield, at a yard full of scrap lumber and rusted car tops, at the hillsides so full of green they looked almost blue. There was a lot to appreciate. I wished I could.

GENE

It was nice in That Woman’s car, but I needed a smoke. I was thinking of that dead man, the screaming woman and her baby.

That Woman said, “Does your sister live in town?”

I said, “She lives in the green house next to Lawyer Dan.”

That Woman nodded. “That’s where you want to go?” she said.

“Yeah,” I said. “I stay in the little house out back.”

The yellow dog licked itself.

I said, “That dog might need to go to the bathroom.”

That Woman said, “She was just out.” She pulled the car to the side of the road.

The little girl said, “Mommy, I want my glass back.”

Dawn said, “Little late for that.”

Little girl said, “Help me find it.”

That Woman hunted something in the floorboard. The dog fidgeted and grunted like this: “Unh unh unh unh unh.”

That Woman said, “I can’t find my phone.”

I said, “You want me to walk your dog a little bit?”

She said, “Gene, yes, I would.” Felt good to hear her call my name. Like somebody scratching between my ears.

The back door hung open where Dawn and her little girl had got out. They rummaged down the side of the road in the gravel. The dog sat there, head pulled forward. I got ahold of its leash. Dog raised its lip. I said, “Come on, Old Yeller, let’s me and you sniff this place out.” The dog come down out of the car. We got off in the grass, and she cut loose with the waterworks. I said to her,

But by then the dog was nosing in the gravel, trying to make her own sense of the world.

DAWN

Aunt June didn’t care much for air conditioning. She liked to keep things natural. All the way to Canard the air whipped through that Honda and our stinks mixed up together—mine, Nicolette’s, Pharoah’s, June’s, and Gene’s.

On the way home, Gene filled June up with stories of every yard he ever mowed, stories more tedious than my husband’s pimple-and-bowel-movement stories, more tedious than him telling me his dreams every morning and the plots of his comic books every night. Gene’s weedeater stories about gas-and-oil ratios and how to keep grass clippings off people’s porches and how he learned to tell the difference between weeds and stuff people had planted on purpose went on without end, and by the time we’d got back to Canard, June had him mowing my mother’s yard.

When we finally got to the foot of the hill in front of Momma’s house, Gene was going on about mowing over a nest of yellowjackets and I said to him,

Mamaw’s Escort parked on the street in front of us, on the other side of Momma’s steps. Mamaw got out, said, “Our Savior, arrived at last.”

June sat both hands on her steering wheel, said, “I can’t believe she’s still driving that thing.”

Mamaw came over and stood to where June couldn’t open the car door without hitting her. Me and Pharoah got out and stood in the street while Nicolette got loose from her car seat. “Do it myself” were Nicolette’s first words and she’d said them ever day since. Mamaw’s eyes fixed on Weedeater, who couldn’t get loose where June had the Honda jammed up against the bank. He’d got his shoulders above the top of the door, but his feet had got tangled up in all that plastic June lay down for him to sit on.

“Mamaw!” Nicolette hollered and ran to who was really my mamaw. Nicolette’s real mamaw—my mother—had not been around enough in the past three years for Nicolette to name her. She just called her Tricia or Trish, which is her name—Tricia Redding Jewell.

Weedeater finally got out and stood on the sidewalk above the bank. He squinted up at Momma’s house, which was at the top of seventy-three concrete steps, seventy-three steps pretty much straight up a hillside in downtown Canard.

Weedeater said, “Some yard.”

Mamaw said, “Who’s this?” standing close to June looking into the side of her head.

Nicolette looked at June like Mamaw was talking about some creature living inside June’s ear. I tapped Nicolette’s shoulder. She tilted her face up at me.

I said, “She’s talking about him,” pointing at Wee

deater.

Nicolette looked at Weedeater, looked at June, then shot over to Mamaw and gave her a hug that might’ve knocked over some. Mamaw said, “Aint that something?”

Nicolette said, “I got to pee.”

GENE

Me and that parade of women headed up the steps and by the top I would have eat that baby for a smoke. I was winded, but That Woman’s mother, they called her Cora, wadn’t even drawing hard. She was built like a roll of rabbit wire and didn’t weigh much more.

“God Almighty,” Cora said from the screened-in porch. The rest of us strung down the steps, me and Dawn furthest down, looking out over town. That Woman said, “What, Momma,” and at the top we seen what.

It was as nice a house as I’d seen without a front door. It had big high ceilings and walls smooth with plaster. It was plain inside, no ductwork or drop ceilings. It was also a trashy mess—piles of frozen dinner and pizza boxes in the living room, clothes strewn, mail strewn. They was a line of sticky drips on the floor from the front door to a commode straight ahead against the back of the house. I tramped through the cans, the bottles, the shot-off fireworks, on my way to the bathroom. Once in there and going, I was afraid my pee would knock the commode through the rottenwood floor. That commode was one of many things not secure in that place.

When I come out of the restroom, Evie Bright stood in the door frame like it was our fault she didn’t have wind enough to get up the steps.

DAWN

“God Amighty,” Evie said. “There aint no point to that.”

I asked her what happened to Momma’s door. Evie was my age, but her and Momma partied together.

Evie said, “I don’t know. Somebody took it.”

I said, “Took a door?”

Evie said, “I don’t know, Dawn. How would I know? I’m not the door-woman. You want to know where the door is, come home and watch the door. Caint see the door from Tennessee, can you? Caint keep an eye on the door from there.”

I walked off. You can’t talk to high people.

Even though she was half my size, Evie used to take up for me. But by the summer of oh-four, she was a quarter my size. And dwindling. In high school though, she’s the one would fight when people would give me shit about how big I was or how I didn’t listen to the right music, or didn’t act like boys were interesting, or how I let my pit hair grow or whatever. Evie didn’t care. In high school, she’d fight for me over stuff she didn’t like about me herself. But it had been a while since high school.

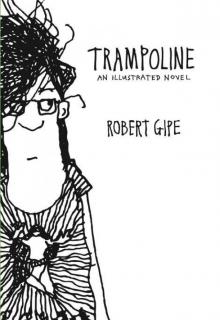

Trampoline: An Illustrated Novel

Trampoline: An Illustrated Novel Weedeater

Weedeater